Finishing up work at Qazi Gol.

The season is wrapping up quickly here and, I think it’s safe to say it was a success. Three weeks goes by very quickly in the field. We spent the last week working at the second site I told you about, now named Qazi Gol.

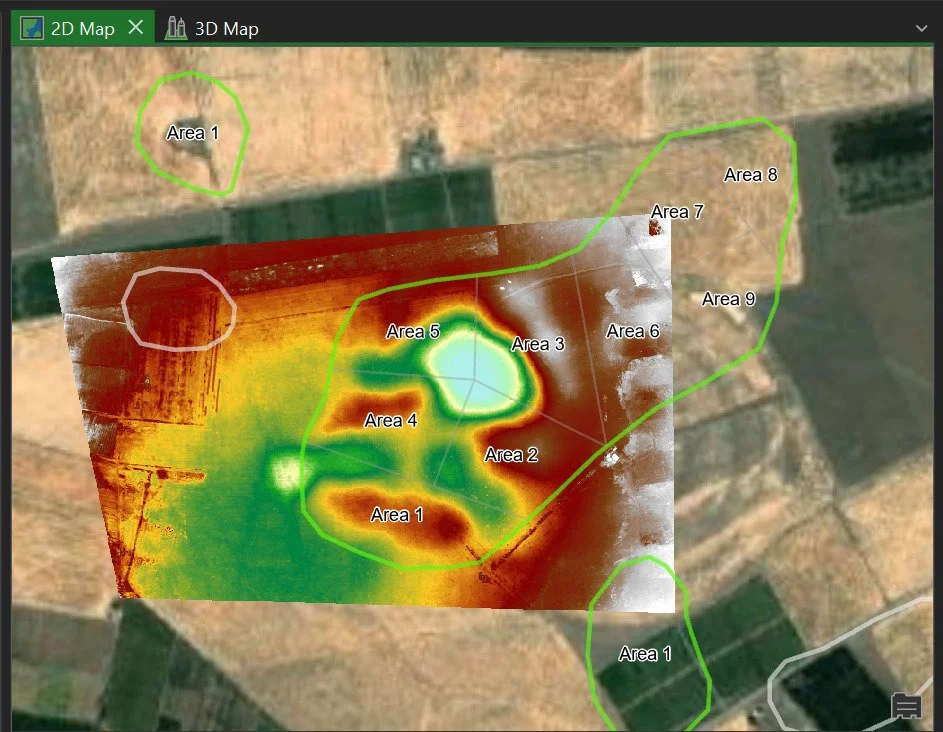

Gol means ‘pond’ or ‘lake’. You can see the outline of the site (light green line) and a light blue or aqua colored area in the center on this topographic map - that is the gol.

Topo plan of Qazi Gol. Blue is low elevation and white is high elevation.

One of the interesting things about this site is that the Gol is human-made. It is an old pit dug for soil or clay that has subsequently filled in over a long period of time. In fact, the white high elevation patch (white) next to it (near the label “Area 3”) is where they dumped all the soil that came out of the pit that wasn’t useful for making mudbricks.

It’s hard to see the elevation change. In this mid-morning photo I was able to use the shadows to highlight the depth of the pond which is about 4 m at its maximum now. We don’t know how deep it was originally excavated.

The date of the Gol’s digging also isn’t clear. It could be Neo-Assyrian, or it could be much later, even a late historic period. We need to come back for more work to figure that out.

Refeeq instructing Ali on how how to balance the FM-256 gradiometer. He is standing on a plastic box to raise the instrument as far as possible above the ground where subsurface interference can make it hard to balance. They are both magnet-free!

An important part of the program was the continued training of the staff at the Directorates in geophysical techniques. I’ve already got a few more archaeologists interested in coming out next year. We had a classroom day to go over some of the basic concepts, how to lay out a field project, and to demonstrate downloading and some data processing in a slightly cooler (and less windy!) place. On the next to last day of fieldwork, Rafeeq and Ali balanced the gradiometer and walked all the survey squares with the machine. I was just a helper — success.

The end of data collection at Qazi Gol on the last day of the fieldwork.

Report writing, data uploads, labeling photographs, packing the depot, saying goodbyes at the Directorates, packing, airports and airplanes. The next 24+ hours are the hard ones. I’ll take a hot, dusty field to Seat 24H any day, but it’s time to head home.

A walk in Erbil

Last Friday I spent much of the day sitting behind my computer working on geophysical training materials for my team. Late in the afternoon I went for a walk around the Ankawa district just to stretch my legs. The temperature was dropping 12 degrees, so I figured it might be a bit windy outside, and it was.. With no rain for months, it was also a dusty, not quite a dust storm, but the streets were oddly quiet and the sky was brown. It was hard to see some of the tops of the taller buildings in the distance. I took some photos to give you a sense of the Ankawa district of the modern city of Erbil. There no agenda in these image; they just struck me as interesting, iconic, or humorous. There are normally a lot more people, and the sky is quite a bit bluer.

What’s in a name?

I often get asked who gets to name archaeological sites. The answer is, “it depends”. Many large sites with either standing architecture or large mounded accumulations of occupational debris creating notable monuments (Kurdish, girdi) in the flat Erbil Plain have names stretching back centuries. Other sites have names commonly used by the locals but rarely put onto maps. The decision about naming a new, otherwise unnamed, site often falls to either the Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage, or to the landowner, or to the archaeologist.

Only one of the seven Sebittu sites actually had a name when I started work here in 2022, Girdi Tandura. It is the only site with a prominent tell and it is immediately adjacent to the village of Tandura. Tandur means ‘bread oven’, so literally ‘Mound of the Oven’.

The mound at Girdi Tandura.

In previous seasons, we established the names of two other sites: Kharaba Tawus (lit. ‘Ruins of the Peacock’) and Sirawa (lit. ‘Place of Garlic’) by asking local landowners or an official called a mukhtar, an Arabic title left over from the Ottoman Empire that denotes the head of a village or a small region. We commonly call on the mukhtar of the region just to let them know we are working here with permission and to ask that our equipment not be disturbed.

This season we have two new site names, both provided by landowners. Site #285 is now called Qazi Gol (lit. Qazi’s Pond, Qazi being a personal name). Qazi Gol is a low-lying spot near the western edge of Site #285 which we are told often fills with water, but not in September after many months of no rain.

The other name is Kharaba Farsa Kuzhraw for Site #292. This name literally translated, I am told by Rafeeq, means ‘Ruins Where Farsa was Killed’. Specifically this name is applied to the location of a water well on the site. I inquired about who Farsa was and got several possible answers. Farsa might have been a recent or historical individual, or Farsa may refer more generically to a horseman in the military. Perhaps it is reference to some specific fight or battle. My sources failed to clarify; perhaps nobody knows the answer.

When I submit my final report to the General Directorate later this week, I believe the names will be made formal, unless there is an objection. With thousands of nameless archaeological ruins, there is not a huge concern with what’s in a name. Except that I find it is easier to remember a name than a serial number, so I would very much like to all the Sebittu sites to be on the map with a locally-acceptable designation.

Some results from Site 292.

We have found our ancient village!

Over the course of a week or so Rafeeq, Ali, and I have collected 134,400 readings of the strength and direction of the Earth’s magnetic field from each of two sensors on our GeoScan FM-256 gradiometer at Site 292. The sensors are positioned on top of one another at either end of 0.5m tube. The sensor at the top serves as effectively a ‘background reading’ while the sensor at the bottom of the tube, closer to the ground, has the same background, plus it measures the effect of buried soils, features, and artifacts (including archaeology!) in roughly the top meter of soil.

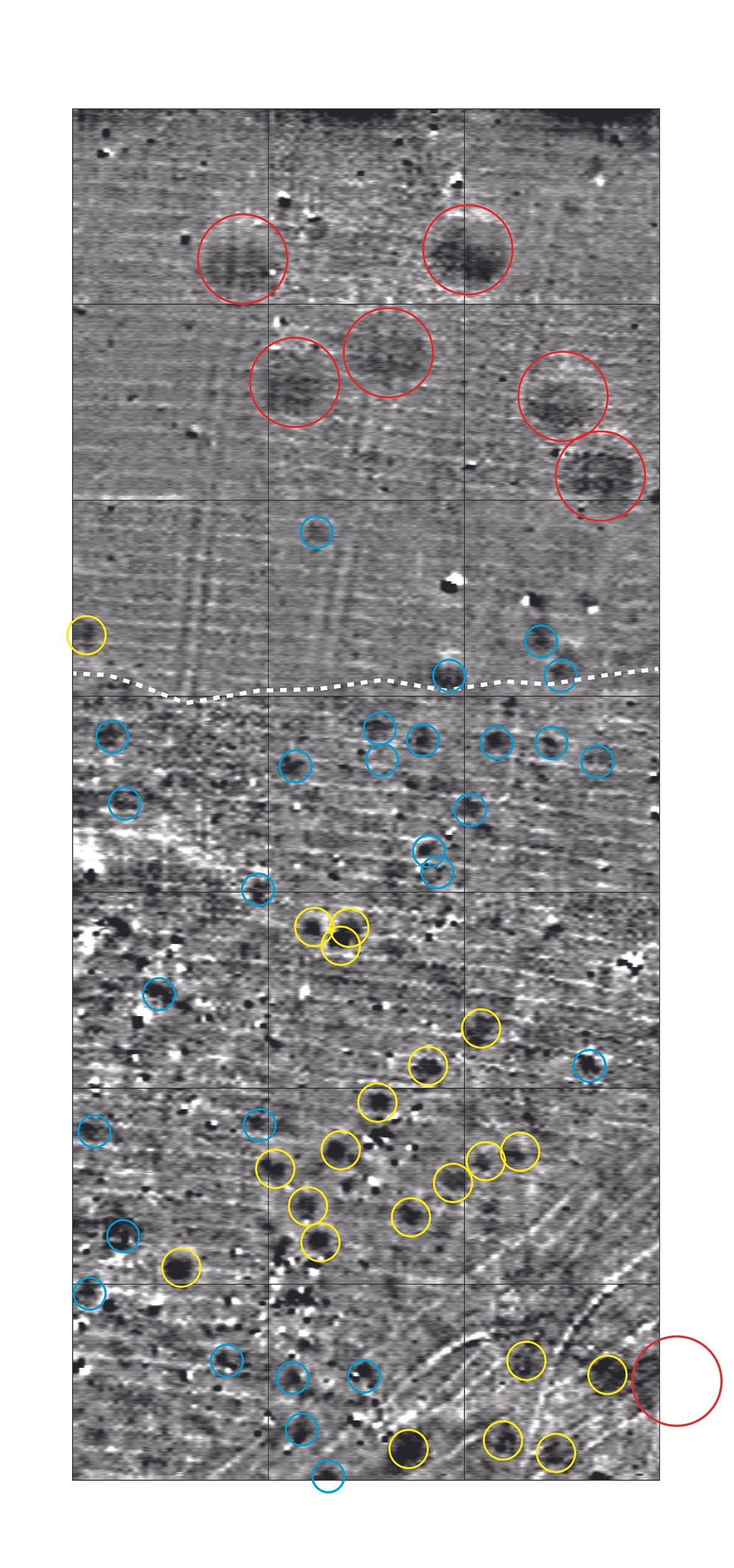

As we collect data, the bottom sensor reading is subtracted from the reading of the top sensor and we see the gradient between the two which has the effect of cancelling out the Earth’s magnetic field leaving only the effects caused by things at or below the surface. The figure below shows a map of Site 292 creating by assigning each of the 134,400 readings a grey scale value. Strongly positive and negative magnetic readings are black and white, while the majority are a shade of grey.

I know this looks like a mess. It is not easy to read the magnetic field gradiometry map. How ever, I’ve been reading these maps from the FM-256 for 25 years now, so I’m able to make pretty reasonable guesses at what we are seeing here. Each pixel in our map represents an area of 12.5 cm x 12.5 cm, and the entire map covers an area of 60m (east-west) by 140m (north-south). So our map is covers just over two acres of land.

The key to interpretation is distinguishing between the “signal”, that is the features we are interested in – ancient features, from the “noise” which is either underlying geology or, more importantly here, the signs modern agricultural practices or modern trash.

All the white lines running roughly east-west are plow scars, and the long parallel linear features running roughly north-south are truck tracks. Likewise, in the bottom right corner (southeast) are tracks from a modern tractor. We know this because we can see them on the surface. These are noise. We can ignore them in our analysis. The plow scars are deep (c. 15cm) so they are prominent. The tire tracks are not and they seem to “disappear” about halfway down from the top of the map because they are only visible in the quieter part of the map.

As you can imagine a modern field has quite a bit of modern trash in it. Plastic bottles, pieces of rubber tires, and other non-ferrous metal have no effect on the gradiometer because they are not magnetic. However, small pieces of iron or steel do and each of the yellow circles represents what is most likely a modern piece of metal. A few might be ancient, but these tend to have a weaker signal that nails, screws, pieces of iron wire, bits of broken plows, and other farming debris.

Finally, at the top of this map – the Noise Map – are three large black features at the very northern edge of the survey area. I didn’t draw them as circles because they are iron poles for carrying electrical wires Despite the fact that they are over 5m away from the edge of our survey area, and they are only about 15cm in a diameter, they are strong magnets that cast a “shadow” way out of proportion to their size. In fact, we can’t survey any closer to them because they would swamp the ancient signal with their noise.

So what’s left after we account for the noise, most likely are the remains of the ancient Site 292.

The seven red circles represent very large pits (roughly 8-9 m in diameter). They don’t appear to be modern because the signal is weak and there is almost no metal in them. We have found clusters of such pits before and they were probably storage pits in the Neo-Assyrian period, possibly for grain. There is one possible storage pit in the southeast corner, but I have my doubts given its proximity to other ancient features. The yellow circle and blue circles are slightly smaller pit-like features. They may have been household storage or trash pits, or even postholes to hold timbers for house construction, although this is unlikely since the Assyrians tended to build in mudbrick. The yellow features are larger than the blues ones, but this may or may not turn out to be important in terms of their ancient functions.

One important feature is that the northern part of the site has far less ancient material and, in general, is a more monotone grey in the gradiometry map, suggesting that it may actually be outside of where people were living day-to-day. The dashed white line is roughly the edge of what seems to me to be the “household area” and beyond it to the north may have been used for other purposes. If the red circles are for grain storage, they would have held a lot of grain!

We don’t see any evidence of mudbrick walls or stone wall foundations, but this is not at all surprising given that this was a very small place occupied for maybe a century or so that was abandoned 2,600 years ago and has been intensively farmed since them. A few of the red, yellow, and blue circles will be our targets for excavation in 2026 when we can really start getting into the details of what the Neo-Assyrian inhabitants of 292 might have been doing all those years ago in this forgotten place.

We are not alone.

Spending a great deal of time standing in a field gives one an opportunity to observe the non-human inhabitants of the Kurdish landscape. We came across an injured fox hiding (and then fleeing) from a vegetable patch when we recently went to visit the site of Sirawa where we worked in 2024. I am pretty sure it was a Kurdish red fox, but I’m no expert. It emerged from the garden and disappeared so quickly despite its injuries I didn’t get a photograph.

The field at Site 292, as you saw in the last post, is pretty barren. There are two plant types that we have been surveying through and over. One is a low thorny bush which I have tentatively identified as (Prosopis farcta) commonly “Syrian mesquite” or . A more common prickly plant that is encountered in Near East surveys is camelthorn, but it doesn’t have the same leaf structure. Rafeeq told me that the mesquite beans are collected for use as medicine by some of the villagers.

Possibly old world mesquite.

Our other botanical friend on site is a pink-flowered field bindweed, which is a relative of the morning glory. They look odd in the harsh summer since the flower appears so delicate, but the plant roots are deep and the seeds viable for years (according to iNaturalist) so it is well adapted to the harsh climate.

Possible field bindweed.

For some time, I’ve been trying to teach myself about birds using an online app and have become somewhat adept at spotting crested larks, Eurasian collared-doves, and red-wattled lapwings on our drives to and from the site. My latest spotting was a western yellow wagtail. While watching my colleague slowly walk up and down 20m survey transects is engaging for the first few hours of the day, there is plenty of time to look around. For geophysical survey we have to be metal-free, so no cell phone photos of the birds either.

Shepherd moving his flock. The goats are in the lead, and sheep follow. Check out those goat ears!

And then there are the domesticates. Frequent visitors include the ubiquitous herds of fat-tailed sheep and long-eared goats, often accompanied by dogs and a shepherd riding a donkey or a horse. Below is a traffic jam on the track to Site 292. All of these species have been here for at least 4,000 years (sheep and goats much longer, with dogs being the oldest domesticate of all). This is entertainment on the Erbil Plain.

On the way home from Site 292.

The team.

We are a small field team at the moment. Magnetic gradiometry survey requires a minimum of three people to run efficiently. One person carries the machine and the other two move a rope painted every meter with marks guiding the operators as we walk our 20m transects.

The gradiometer is set to take eight samples every meter along the transect. Rather than having to press a button for every reading (160 readings per transect!), the FM-256 automatically takes a reading with the trigger set on a timer. The machine beeps at a regular pace on the first of every eight readings. So, as the operator walks, the key is to make sure the machine beeps at the painted marks on the rope. Thus collecting readings at regular intervals. It sounds tedious, but after a few dozen miles of walking at exactly the same pace, it becomes routine.

Ali, Refeeq, and Ahmet at Site 292.

Our crew for this project includes Rafeeq Bradosti who, along with me, carries the gradiometer. He is pictured in the center above. Rafeeq is an archaeologist with the General Directorate of Antiquities and Heritage. I’ve worked with him since 2023. Ali Banisharani, on the left, is an archaeologist from the Erbil Directorate and is new to the team. We also have had two drivers for the project this year. Ahmet, on the right, has just joined us at Site 292 a few days ago, although he has worked with me before. Below is Salar who switches off with Ahmet. They both work at Korek Private Hire and are invaluable members of our team fighting both the traffic of Erbil and the rutted tracks of the countryside to get us here and home safely.

Salar at Site 292.

Meet Site 292

In an earlier post (“The Slow March of Science” 9/21/24), I talked some about the use of magnetic field gradiometry as a way of gathering data about what is immediately below the ground without excavation. A handheld gradiometer measures minute fluctuations of the Earth’s magnetic field caused by buried artifacts, features, and changing soil types. Human activities such as building, burning things, and trash disposal alter the magnetic properties of soil in predictable ways allowing us to tell something of what happened in a place quickly. Archaeologists often use geophysical maps to determine the best place to dig.

Sunrise over Site 292. This is not a pretty site, and it is impossible to avoid the tangle of power lines as the site is bisected by major electrical transmission lines.

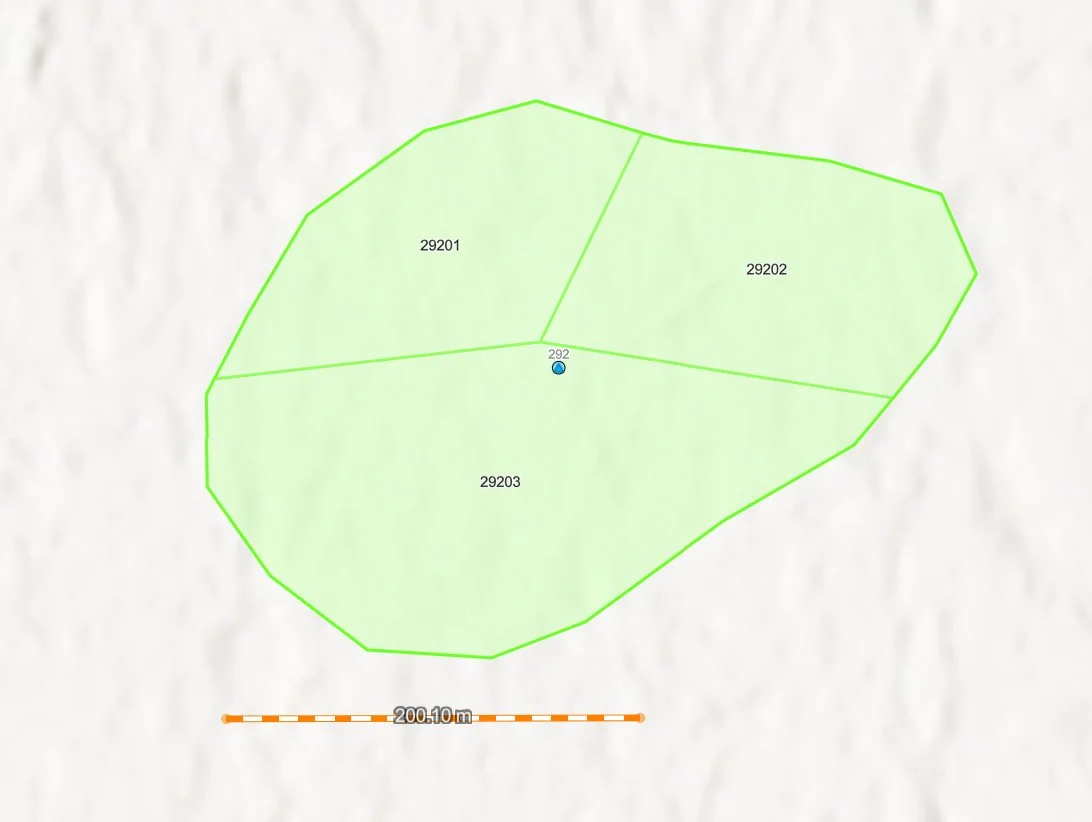

The terms ‘flat’ and ‘nondescript’ fit Site 292 perfectly. The archaeological site covers an area of 6.74 hectares (16.7 acres) as mapped by the EPAS team. They divided the site into three parts during their surface survey in 2017, noting that Neo-Assyrian pottery only came from their Sectors 02 and 03, reducing the site of the Neo-Assyrian settlement to 5.14 hectares (12.7 acres).

This is the map from which we are starting. The site was identified via satellite imagery by EPAS, and divided into three sectors for surface collection.

That is still a large area to survey. Excavation over such an area would take decades — we need to narrow our search for the right spot to dig. In Sector 02, the EPAS team found pottery from other time periods apart from the Neo-Assyrian (c. 900 – 600 BC): the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (covering together roughly the time period of 2000 - 1200 BC), and a later occupation dating to the Parthian/Roman period (roughly mid-3rd century BC to mid-3rd century AD). Sector 03, on the other hand, was noted as only having Neo-Assyrian remains, so we started with this part of the site to avoid complications. Our survey area is in the southwestern corner of the site.

Site 292 from the road looking to the southwest.

In this photo you can see (if you look very, very closely) in the middle of the field a slight change in color to the soil (it is whiter in general) and a very slight rise in elevation. These are the kinds of subtle changes that archaeologists use to locate smaller settlements like Site 292. We are surveying on the higher ground where the soil colors indicate different soil formations. With luck, some remains from the Neo-Assyrian occupation will still be present in fields that have been intensively cultivated for centuries.

Back in Erbil

Welcome back to everyone who has been following the Sebittu Project on my blog. After a wild ride this past year, it is great to be back on the Erbil Plain and starting our third season of archaeological fieldwork. The seven small Neo-Assyrian settlements (c, 900 – 600 BC) of the Sebittu Project cluster together about an hour’s drive southwest of Erbil (ancient Arbela) now the capital of the Kurdish Region of Iraq and once an important city of ancient Assyria and an UNESCO world heritage site.

For those of you just joining the blog, you might want to check out some of my earlier posts for background on our project: Welcome to the Sebittu Project (8/10/2023), Our Morning Routine (8/29/2023), and The Slow March of Science (9/21/2024) are good starting points.

Our overarching goal is an attempt to understand what life was like in the farmsteads, hamlets, and villages of the Neo-Assyrian countryside – who lived there, what their houses were like, what did they eat, what goods did they produce, and with whom did they trade and interact. These seem like pretty basic things for archaeologists to know about the ancient Assyrians and, in fact, we do know quite a bit already about these topics. However, much of what archaeologists and historians have learned comes from written cuneiform texts and the excavation of elite structures like palaces, temples, and the homes of the rich. In other words, it’s a top-down story. The Sebittu Project aims to fill in the some holes in our knowledge by focusing on the unassuming, commonplace, and often drab items that form the archaeological record of everyday life in ancient Assyria.

View of the Erbil Plain from the top of the ancient site of Girdi Tandura in 2025. The wadi (small river) and irrigated fields on the right of the photo contrast with the dry, brown un-irrigated fields on the right. The plain is a patchwork of these contrasting colors. Water is a major concern today, as it was in the Iron Age.

This year I am focused on mapping the houses and other archaeological features at sites in the Sebittu area. Like in 2023, I am using a technology called magnetic field gradiometry to map these subsurface features without excavation. The geophysical maps will then help us locate the best spots for excavation in our 2026 field season. If you look back at last year’s posts, you will see the first map ever made of the Neo-Assyrian hamlet of Sirawa (that is it’s modern name, not what the residents called it in the 7th century BC).

At the moment I am targeting a new site – currently called Site 292 (we’ll get it a proper name soon) – about which we know three things: where it was located, that it was inhabited in Neo-Assyrian times, and roughly how big it was. We know these from pottery found during previous surface surveys conducted by another team (EPAS) in 2017. Before then, Site 292 was unknown to scholars, although local farmers would have noticed lots of broken pot sherds scattered on the ground as they plowed and worked the land for the twenty-six centuries since the site was abandoned.

Street scene in Erbil early in the morning on the way to work. Erbil is rapidly expanding modern city that is home to roughly a million people. Housing and other infrastructure is being constructed for significant growth as people are drawn to Erbil for work.

The slow march of science.

It has been a while since my last post so I want to catch you up on our progress. We have fallen into a very productive, methodical routine for collecting field data. With temperatures coming down quite a bit over the past week, we are able to work later into the day. We even had clouds and a very brief rain storm yesterday.

Sunrise over the Erbil Plain on the first day of autumn.

Part of my plan for this season was to start to train some of the archaeologists at the Directorates of Antiquities and Heritage in the use of geophysical surveying. To that end, Rafeeq Bardosti on our team has been learning the basics of these techniques. We started with the easy part – data collection. This involves carrying a handheld magnetic field gradiometer perfectly in a vertical position without letting it swing while walking at an exactly even pace in a straight line for 20m, then turning around doing the same thing in the opposite direction, for hours. It is not very exciting to watch.

Rafeeq collecting gradiometry data at Site 298 (Sirawa). Abdullah (in the background) and I are moving the rope (painted with marks at each meter) that Rafeeq is walking along. Once he finished this line of data, we shift the rope 50cm to the east and he walks back towards Abdullah. The gradiometer beeps at each meter mark. Forty lines of data per grid square. It is pretty hypnotic.

Yesterday, we went over a slightly trickier procedure, which is I showed Rafeeq how to balance the machine so that the two sensors use to measure a gradient of the Earth’s magnetic field are precisely located above each other along a 0.5m long tube. Rafeeq has watched me do this all season – tomorrow morning it is his turn! It is one thing to watch and another to master this step. I also demonstrated how to transfer the data from the gradiometer to the computer with Rafeeq today. Those are the three basic field steps. He is really sharp and has picked up quickly – and he has a steadier hand than I do in carrying the machine.

Drone image of the work area on Site 298. The northern edge of the site has been badly eroded and much of the site is lost. There is a canal to the north of the site that has moved through time and at one point appears to have come far south and cut into the ancient remains.

Here are what the results look like. This is largely unprocessed data, but it gives you some sense of the slow march of science. We collect three to five 20m x 20m grid squares each day, slowly moving across the site. This map shows the best 172,800 data points we’ve collected at Site 298.

Which reminds me, we have a name for Site 298 from one of the locals: Sirawa (literally ‘the place of garlic’) which is not very creative since it is also the name of the nearest village, but it is now the name of this ancient place. We are almost certain to never know what the Assyrians called this small hamlet as it was probably never important enough to be written down.

The map is a drone photo taken by Jason from EPAS for us. The red line is the current site boundary, which we have modified since starting work this season. The light red shading in the SE is an area that we added after doing a quick survey of pottery in the region, so our site is getting bigger. The gridded gray overlay is the current gradiometry data (the light blue squares are not yet collected). There may be some buildings in the data, but the main features are a number of large pits (black circles) which have a strong signature because the soil inside has been magnetically enhanced through human activity. The question for next season is whether or not they are Iron Age in date. With this map in hand, we can find their exact location in the flat, featureless agricultural fields and start the excavations at Sirawa.

A good cleaning.

In addition to collecting geophysical data from Site 298, my afternoons, evenings, and Fridays are also busy times when I can work on the material excavated during the 2023 season. Last year we found three small artifact in our surveys and excavations that were interesting enough for a good cleaning, or in more archaeological terms, for conservation.

SP 00002. Coin before conservation.

Conservation is a specialization in archaeology with the goal of preserving the artifacts once they are removed from the soil via excavation (or more rarely, found on the surface). Underground, many materials will decay or decompose when first buried but eventually they reach a stable state with their immediate surroundings (“microenvironment”). Once this stage is reached decay is so slow that artifacts can survive for thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of years. Caves and bogs are good examples of environments where microenvironments form in which many organic materials survive that would normally be lost.

Conservators work to stabilize the artifact (i.e., stop the decay and physically support the artifact), clean the artifact so it can be studied, and then to preserve them through creating a new microenvironment in which the artifacts will survive. Archaeological conservators (not ‘conservationists’) undergo a rigorous training in chemistry and materials science. In Erbil, there is an excellent conservation facility at The Iraqi Institute for the Conservation of Antiquities and Heritage, originally funded by a US Department of State grant in 2008 and now a full-functioning facility.

An archaeology colleague of mine at the Iraqi Institute, Aram Mohammed Amin, agreed to conserve our three small artifacts and I left them with his team at the end of the last season. I just got them back from their secure storage location in the Museum of Antiquities and Heritage.

SP 00002. After cleaning. I used a raking light in this photograph to highlight the imagery on the surface. This is just a candid shot. A formal photograph with normal lighting and a scale will be made, along with a drawing of both sides of the coin. My goal here was to highlight how much can be hidden beneath a good layer of corrosion.

SP 00002 was found in the plow zone at Kharaba Tawus and, yes, this was the second artifact we found on the project. I only have one side of the coin photographed here, but you can see how the coin is now legible and can be dated by an expert in medieval numismatics. It will be stored in the Museum under archival conditions so future scholars can make a careful study of the coin for decades to come. It is made of copper and one of our archaeologists last season suggested it might date from the ‘Abassid Caliphate between AD 750 and 1258. I’m no expert on coins, so don’t quote me on that, but I’m sure we will be able to date this one now that the conservators have been able to remove the copper corrosion and stabilize the artifact.

Anyone who knows of a good parallel, please let me know!

Site #298.

We have been working for three days now at Site #298. We still don’t have a modern name for the site, but we are meeting up next week with the muhktar of a nearby town who will probably be able to provide us with a local name. Until then, it is just Site #298. The ancient site was first recorded archaeologically in 2016 by the EPAS team after identifying the location as a possible ancient site via satellite drone imagery.

According to the EPAS surveys, Site #298 was inhabited only in the Iron Age and is just under 2 ha in size. While the Sebittu Project has not yet done any systematic surface survey, we did find a type of jar handle that is often equated with Roman assemblages and a thick piece of colored glass with a thick patina caused by the weathering of exposed glass which may be Islamic in date. Both were in the southern part of Site #298. So, there may be some later deposits here, but a single sherd and glass fragment from the surface are hardly enough evidence to build a strong case. Surveying is a cumulative process and initial assessments are often refined as new information is gathered.

As you can see in this photo, Site #298 is covered in sparse vegetation, a few spiny bushes, the remains of a wheat harvest, and a few willows. These are good conditions for doing survey work as there are few modern constructions and the ground is generally flat.

Site #298 from the south. You can just barely see the ruins of the important Assyrian city of Kilizu (modern Qasr Shemamok) being excavated by a French team. That large mounded site is just behind the modern village on the far left of the photograph.

Our morning routine is to leave the dig house at 4:45am with Bapir, Rafeeq, and I meeting up to take the car on the hour long commute west to Site #298. We pick up Tara at a point near her house in Erbil and, after stopping for hot bread and cold ice (both field necessities), we arrive at the site a few minutes before 6 and immediately set to work.

We are using a hand-held device called a magnetic field gradiometer to measure minute fluctuations in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by features immediately below the ground surface. Our device can map down to about 1.0 – 1.5m in depth (which is called the “shallow subsurface”) and can detect iron ferrous alloy artifacts, burnt materials that contain iron such as clay (so we can find hearths and ovens), and more subtle differences between soil types (e.g., pit fills often have an enhanced magnetic signature due to various human activities). More on that later.

FM-256 gradiometer, me, Rafeeq, and Tara at Site #298. Note that the humans are all dressed for fieldwork in the hot Kurdish sun: hats, long sleeves, as little skin showing as possible. It takes time for visitors to acclimate to working in these conditions.

We lay out 20 m by 20m grid squares on the ground and then carry the machine back and forth across the square at 50cm intervals taking measurements of the earth’s magnetic field. The gradiometer collects the data which is then transferred to a computer where I process the data and map the results. I takes us about an hour to collect one grid square, so there is a lot of walking, and a lot of moving of tapes and ropes to keep us collecting data on the grid.

This is a typical dataset from a 20m x 20m square at Site #298. The white and black features are strong positive or negative magnetic readings. Where we see both a strong positive and strong negative together, we are looking at both ends of a magnet of some type, like in the lower left-hand corner of this image. The large black circle is probably a pit -- ancient or modern is hard to say from this image alone. The smaller black holes are also pits.

We stop mid-morning to have a field breakfast in the shade of the car (those willows are not very shady). These are rough field conditions: the gradiometer case is our table and even by breakfast it is well over 100ºF. Typically breakfast is now warmish bread I mentioned earlier, tomatoes, cucumbers, cheese, and some canned tuna. Tara and Rafeeq sometimes bring treats from home.

Tara, Bapir, and Rafeeq sharing breakfast in the limited shade at Site #298.

Then back to work until the heat gets to be too much. After a number of years of doing survey with this particular gradiometer, I have come to appreciate that it does not collect good data when it gets too hot – and without shade in the field we are in the direct sunlight 100% of the time. I’ve been logging field temperatures and comparing them to data set quality and it seems that over 100ºF there is an increase in noise in our datasets and above 107ºF we have yet to collect any acceptable data. Fortunately for us, the end of the summer heat is in sight and daily temperatures will plunge into the low 90s and the nights get much cooler by the end of next week, which will extend how long we can work. Normally, fieldwork ends between 12:30 and 1:00pm and we head home for lunch and a siesta. Then work in the dighouse on fieldnotes, datasets, report writing, and emails until an early bedtime.

Cornfields in Assyria.

Stamped and signed letters in hand, we made the rounds of regional Asayish and government offices to ensure that everyone knows who we are, what we are doing, and that we have official papers documenting our permission to work. That finished, Bapir, Rafeeq and I drove southwest from Erbil to visit each of the seven Sebittu Project sites and make a determination of where we want to work this season. There is a map of the location of the sites on my website here.

All seven sites are at least in part being used as contemporary agricultural land and it is very unpredictable where summer crops will be grown. Often farmers will plant crops in a field for a few years, and then let it go fallow, while at other times they will try a get two or even three summer crops out of the same field. This year is a year of corn. Maize is a New World crop, so it is an invasive species brought back to Europe and the Old World starting the 15th century AD. Why corn now? One of my local informants suggested that Kurdistan normally gets much of its corn from Ukraine and the war in that country has created a strong need for locally-grown corn in northern Iraq. It is a water-intensive crop, so new wells, pumps, and irrigation pipes are proliferating.

Below is a photograph of the site of Kharaba Tawus in September 2023 as our team, under the direction of Dr. Mary Shepperson, excavated some Neo-Assyrian features at the site.

Excavations at Kharaba Tawus in 2023.

Here was that exact same spot yesterday. The cornfield covers many hectares and behind me when I took this photo was a very large irrigation pond (nicknamed “fish ponds” locally) where water was stored to irrigate the fields and fish are grown for local consumption.

Kharaba Tawus in 2024.

Corn is intruding on several other Sebittu sites this year. We also saw extensive summer vegetable patches, and even fields of parsley. The summer in Iraqi Kurdistan is brutally hot (today reached 108ºF) with cloudless and rainless skies. All summer crops are grown via irrigation which is often destructive for the underlying archaeology, so the increased use of irrigation channels is one of the reasons we want to document the ancient landscape before it is gone.

Parsley being grown on Site 285.

After seeing all the sites and evaluating the practicality of working there, and the potential for interesting results, I have decided to start at Site #298. It is a hamlet of less that 2 ha. We’ve worked at a larger village and a smaller farmstead, so this gives us some baseline data on all three site sizes. It is also the only site where all the surface pottery is Neo-Assyrian in date. Finally, while there is not corn on the site itself, there are cornfields nearby that have expanded from last year, so this might be a good time to get the survey done before the corn invades. I’ll post some results from the geophysical survey at Site #298 soon.

A formal beginning.

Sunday morning was spent in a series of meetings with officials from the government agencies who host and support the Sebittu Project. First I met with Kaify Mustafa Ali, the Director General for Antiquities and Heritage for Iraqi Kurdistan (below) and his staff, and then with Nader Babakr, the Director of the Erbil Directorate for Antiquities and Heritage who is in charge of archaeological activity in the Erbil governate. Partly these meetings are formalities to request support and provide updates to the directors about our work, and partly they are social events to reunite with friends and colleagues. There were lots of details and logistics to discuss. Importantly, I learned that two of my team from last year -- Rafeeq Bradosti and Tara Othman -- will be joining me in the field this year both as government representatives, and to help with the field work.

Me and Kak Kaify catching up.

We completed the necessary paperwork that we will need tomorrow to inform local authorities of our presence and activities. The Kurdish security forces, Asayish, keep careful watch over the archaeological projects spread throughout Kurdistan and we will report to them tomorrow morning with the letters drafted today at the Directorate. We will also visit the local authorities in the Sebittu Project area, including the heads of villages (muhktar) near our sites. The rest of our early afternoon was taken up with lunch and a bit of shopping for supplies before heading back to the dig house to get ready for tomorrow. I thought a few street scenes from Erbil would give you a sense of what is going on in the big city.

Ready to help with heavy purchases in the market. We were only buying plastic bags... maybe next time.

Selling figs in the market.

Back in Erbil.

Where to start? This blog post is a short chronicle of an archaeological expedition to the Near East where I have worked as a field archaeologist for a long time. My first trip to the Near East was as an undergraduate student back in 1984, so it has been a 40-years-long journey. As many of you know, I have long been interested in the ancient empire of the Assyrians and this project continues that interest.

From 1997 to 2014, I directed a expedition to a site in southeastern Turkey called Ziyaret Tepe, the Assyrian city of Tušhan. (see that blog here). Tušhan was a large administrative center of the Assyrian Empire (roughly 9th-7th century BC) and our excavations and surveys revealed a wealth of information about how the empire functioned economically and militarily. We found a palace, imperial storerooms and administrative buildings, and an elaborate fortification system. What we didn’t find much evidence for the lives of commoners in the empire. My new project is an attempt to redress that shortcoming.

In 2022, I started groundwork for a new expedition, the Sebittu Project, which is a multi-year international project aimed at documenting life in the smallest of Assyrian settlements. While archaeologists have excavated Assyrian sites of all sizes, there is a clear bias against digging small sites, which I classify as village, hamlets, and farmsteads (more on that later).

I moved my fieldwork to the Erbil Plain in the Kurdish Autonomous Region of Iraq for a number of reasons. First, following the defeat of the ISIS, the regional government in Kurdistan welcomed archaeologists back to a part of the Near East that had been difficult to work in for decades for political reasons. A number of large-scale survey projects fanned out across Iraqi Kurdistan recording the condition of ancient sites we already knew about, and recording thousands of sites that were previously unknown to archaeologists. One of those survey projects, Harvard University’s Erbil Plain Archaeological Survey (EPAS) directed by Dr. Jason Ur was one of those projects. It was the EPAS survey data that was my starting point. Rather than starting from scratch, I used the EPAS database to find sites that might be suitable for exploring rural life in ancient Assyria.

Another reason I came to the Erbil Plain was that I wanted to work in the imperial Assyrian heartland. As the empire expanded, the needs of the great imperial capitals (Nineveh is best known of these cities) grew tremendously requiring an influx of workers many of whom lived in small villages, hamlets, and farmsteads that were founded during this time period. In 2022, I toured a number of sites in the Erbil region, settling on a cluster of seven unassuming ancient sites in a large plain west of the modern city of Erbil that fit my criteria for examining rural life in the Assyrian empire.

Last autumn, three colleagues and I set out to show that this project was feasible given that small sites, almost all of which are located in modern farmland, are often not well preserved. This was a pilot project that needed to answer a simple question: is the information we need still intact under the modern plowzone. The older entries in this blog document that season. The short answer was: yes.

Archaeology is field of tantalizing intellectual questions, and brutal pragmatics. Excavations are very expensive and funding for primary field research in archaeology is scarce. I have a lot of brilliant colleagues out there competing for the same limited pool of funding. Unfortunately, I drew the short straw in 2024 and was unsuccessful in my major funding requests.

However, my mentor (whose motto was “archaeology is the art of the possible”) drove home the importance of keeping a presence in the field and making progress even on a limited scale. So, I scraped together a modest sum of research dollars, packed my bags full of geophysical survey equipment, computers and other gear (padded with a few requisite clothes) and have come to Erbil to try and map the subsurface remains at two the Sebittu Project sites in anticipation of better fortunes for funding next year. With any luck, I will have the partial plans of two ancient Assyrian hamlets that will guide our future selection of excavation units in the 2025 field season. Check back here for updates as the field project unfolds.

I made it to the dig house late on Saturday after a very long flight. First things first, check all the gear and make sure that nothing was broken or lost in transport. Everything looks good. Now, time for a long rest

Old tech with a new twist.

Less than a kilometer south of Kharaba Tawus, at a lower elevation near the modern road, there are a series of mudbrick buildings standing in contrast to the modern cinder block constructions that make up the majority of structures on the western Erbil plain. We identified them a brick kilns where the ancient technology of handmade fired brickmaking was still practiced, but with a few modern twists. Seeing activity down at the kilns, one morning Mary, Rafeeq, and I took an hour away from the excavations to investigate and learn about this craft.

We met Qasim and his assistant at their brick kiln, There were in the final process of stacking the kiln with 40,000 sun-dried but not-yet-fired bricks, all made by hand in moulds and ready to be fired. The doorway underneath Qasim (dress in black) leads into the kiln interior but it is blocked with bricks. In fact, the entire structure they are standing on is filled with bricks. They were just putting on the last few rows. Over the following days they would cover all the top bricks with a thick layer of mud plaster, sealing the kiln. Qasim’s assistant has staged bricks next to him that he is handing up six or eight at time to Qasim. On the left are a pile of finished, baked bricks ready for use.

The bricks are made with clay dug up in a pit about a kilometer or so away from the kiln, mixed with straw brought in from the fields, and water. You can see that the recipe is pretty variable. The straw helps keep the bricks from cracking during firing and cooling. When they are fired, the straw has been burnt away, but leaves a negative impression on the clay. We see this tell-tale impression on bricks (both fired and sun-dried) dating all the way back to the Neolithic. Old tech!

Here are bricks that have been formed in rough wooden moulds and stacked to let them air and sun dry. Once thoroughly dried, they can be put in the kiln. Putting bricks that still have water in their cores into the kiln causes them to explode upon exposure to high heat. These bricks are laid out on a specially prepared surface made of animal dung and straw that can be pressed into a flat surface to which the bricks don’t stick when still wet. The small pile of material in the left background of this photo is actually a pile of straw ready for use in brick making.

So the bricks are made and dried. They are stacked in a vast organized heap filling the inside of the kiln, which is in essence a square room with brick walls covered in mudplaster. The kiln is sealed at the top. How does the firing work?

We went to a second nearby kiln that was empty to document the interior of the firing chamber. Below the kiln is a large open space, another entire room, that has a grill-like ceiling leading into the kiln. Here you can see the openings leading from this below-ground firing chamber into the kiln. The bricks were stacked over and on top of the grill openings with enough space between them to allow the passage of hot air between the bricks during firing. This is what Qasim’s kiln looks like when it’s empty.

Around the side of the kiln is a passage that leads down into the firing chamber, which has two parts. One is the room below the kiln with the grill-like ceiling. This subterranean room conducts the heat up into the kiln. The second part is where Rafeeq is heading in this photo. It is the room where the fire is set. The walls are charred from intense heat. The fire in this chamber will burn for three days, according to Qasim, driving all the remaining water out of the bricks and slightly fusing the clay-mud mixture into a durable, permanent brick.

This is where the technological twist comes in. In ancient times, the kiln would have been fired with wood, brush, or animal dung which had been prepared for use as fuel. The modern countryside is largely devoid of wood and while animal dung is still used for some domestic tasks, it has largely been replaced for use in brick making by an energy source plentiful in the region — petrol.

This picture might seem oddly out of place, but it is actually quite important. The modern brick kilns use old clothing to soak up the petrol for firing the kilns. For three days, that small chamber will, in essence, be fed gasoline-soaked rags to keep the fire burning hot and even enough to fire the stacked bricks. This process involves no advanced machinery to run; the skill of the brickmaker ensures that the bricks are fired long enough for them to be fully strengthened but not too long that they are ruined in the process. These kilns, like those in ancient times, could be overfired, ruining the bricks and the kiln itself, and creating a hard, spongy mass we call slag. Ruined bricks and pottery are called wasters and when we find wasters at an archaeological site, we know that the ancient inhabitants had used such kilns to make bricks, pottery, metals, or other materials requiring the controlled use of high heat.

We were told that the firing of Qasim’s brick kiln was going to happen in the next few days, so stay tuned to see how it all works out.

Familiar and not so familiar.

One of the fun puzzles in archaeology is when you find something that you don’t immediately recognize. Most of the artifacts we find are broken, often shattered into tiny pieces, which makes the puzzle even harder to sort out. Through laboratory study we can often determine some of the functions of an artifact, collecting data on the tiny scratches left on stone or metal tools when they were used (called “microwear”) or by comparing ancient artifacts with historic, or even modern, parallels (called “comparanda”). We scour through reports written by our colleagues for similar artifacts, and sometimes we take samples of residues still adhering to the tools that provide more information on their function.

Top side of the celt showing careful working of the stone. The artifact is also weathered suggesting at some point it was exposed on the ground surface.

Here is the working edge.

This is a stone tool, 5 cm long, made of a very fine-grained stone. It has been laboriously shaped by using a harder stone to peck away at the original piece to produce a symmetrical tapered tool with a straight cutting edge on one end. They tend to be widest just behind the cutting edge, tapering in a bit as towards the edge.

Everyone on my team instantly recognized this as a “celt” in archaeological terminology. Celts come in many sizes and with numerous variations in shape. They were produced in prehistory across the ancient Near East and were eventually replaced functionally by copper and bronze tools. For anyone who does heritage woodworking, this is probably a recognizable tool, used much as modern hand chisels are for shaving, cutting, and shaping wood.

This was found at Kharaba Tawus and it was probably made between 6000 and 4500 BC. We know that Kharaba Tawus was occupied at this time because the site has produced a large number of prehistoric sherds of the Halaf and Northern Ubaid ceramic traditions. These well-documented painted pottery types are very distinctive and tell us that long before the Iron Age, this place housed a prehistoric settlement that forms the bottom layers of the low rise we are excavating.

The view shows the broken section of the artifact (the other side is smooth and finished). You can see the red area immediately below the blackened surface.

Less obvious is this limestone object about 12 cm in diameter and 5.5 cm thick, also found at Kharaba Tawus. It is clearly shaped with a short round base and a wide round top which flares out to form a shallow concave surface. The stone is a type we call “Mosul marble”. We are not sure what this object was used for, but the surface has clearly been burned. In fact, a red layer can clearly be seen penetrating the stone about 1.5cm below the burnt surface, which suggests that something might have been repeatedly burnt in the shallow concave dish at the top.

One possibility is that this artifact might have been an incense burner, an object we know was used in religious practices in various cultures across the ancient Near East. The stone is not local, so it was either brought to Kharaba Tawus as a raw material, or perhaps as a finished artifact. Once we are back in our offices we will start the process of looking for comparanda from other excavations to help us provide a date, function, and cultural affiliation for this curious find. If anyone has an idea or a good parallel, feel free to email me.

Unexpected find.

Please be advised that this blog post contains photographs of human burials.

Our progress on the excavations at Kharaba Tawus was slowed by the discovery of several infant burials at the bottom of the plowzone at the site. Finding late unmarked graves is a common occurrence as archaeological sites are typically found on high ground, or on anthropogenic mounds created through long-term occupation in which the decay of mudbrick houses accumulates over centuries or even millennia of use. After settlements are abandoned and the buildings decayed, such high places are often chosen for informal burial grounds by locals and visitors alike.

We cannot say for certain when the burials were cut into the collapsed buildings of Kharaba Tawus. Modern plowing has truncated the burials, the locations of which were sometimes originally covered by a stone or a few potsherds. One of the infant burials was cut into an ancient pit which we think may be of Iron Age date, so that burial was later in time than the pit. If we are correct that the pit was of Iron Age date, then the burials must be more recent than the pit. Archaeologists would say that the Iron Age the terminus post quem.

This burial, possible of a neonate was badly disturbed in antiquity and few bones remain intact. The size and fragility of infant bones makes their preservation much less common than adult human bones.

That said, 2500 years separates the end of the Iron Age from the beginning of modern plowing, so our dating is very rough at this point. None of the burials contained any burial goods like pottery that would have helped us date the burials. The orientation of the bodies may suggest that they are Islamic which would narrow down the possible dates to the last 1300 years, but that is still a large date range.

This infant burial was also badly disturbed in antiquity. The cut made for the burial was deep and very narrow. In ancient times, infant mortality rates were very high. Although precise figures are not available, some scholars suggest that pre-modern mortality rates were as high as between one-third and half of children not surviving infancy.

In consultation with our government representatives, it was decided that given the unknown age but likely antiquity of the burials, the most appropriate action was to clean and briefly record the skeletons in situ, and then to collect the bones and ask our Kurdish colleagues to rebury them. We were informed that this was acceptable to local religious leaders and in line with common practice on archaeological sites in the region.

Our morning routine.

I arrived in Erbil two weeks ago and the workday has now settled into a comfortable routine for the most part. We start work at sunrise to take advantage of the relative cool and leave the field when the heat gets too intense to work efficiently. We seem to have settled on 108 degrees F as our upper threshold, which took us back towards the dig house at 10:30 or 11:00am when we first started work. The temperatures have cooled a bit the last few days and as we slip into September, we will be able to work later into the early afternoon. Of course, sunrise will also be later, so we will have to start later as well.

Most of us are up around 3am to get ready for the day – tea and coffee, packing up supplies and equipment for the day, a nice cool shower. Our driver, Ahmet, arrives with the team bus at 4am and we all pile in for the long commute to the site.

The dig bus. Comfortably fits eight of us, our driver, and the equipment we need for the day.

After stopping at the Directorate to pick up our four Kurdish archaeologists, the bus makes two essential stops for our workday. First, we buy ice and water from a pleasant older man who sets up outside a hardware store with a palette loaded with large slabs of ice which he breaks up with a crowbar to fill our ice chests and bottles of water.

Next, we stop at a roadside bakery where fresh bread shaped kind of like pita is made in a simple brick oven, at an industrial rate. It is a popular spot for laborers and the bread disappears as soon as it is pulled from the fire. Our bus smells like hot bread for the remainder of the journey. Sometimes there is vendor selling hot chickpeas and beans, which we pick up as a supplement for our site breakfast. With cold water and food acquired, we head through the village to Mastawa and on to our dig site.

Roadside bakery on the outskirts of Erbil. They open at 3am! There is no menu, just bread.

By the time we get to Kharaba Tawus, the workmen have already arrived from the local village in their pickup truck and usually the tents are up and the picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows are waiting to start work. As the sun rises, we are awake and focused and work starts in earnest. We seem to always be racing the sun and the heat, but I find the quiet mornings are perfect for digging.

Sunrise on the western Erbil plains. In summer there is a permanent haze in the sky from the oil wells that support the economy of Iraqi Kurdistan. The flames from gas flaring, as well as the dust raised from the baked earth, both contribute to the haze, and make for spectacular sunrises.

Breaking ground.

As you know, the Sebittu Project involves survey and excavation at seven sites clustered in the western Erbil plain. After I arrived in Kurdistan, one of the first items on my long to-do list was to visit each site and assess the field conditions at present. The spring was relatively wet here, so the winter crops like wheat were good and there was plenty of grazing for the herds of goats and sheep kept by the farmers. While good news, this presented us with a challenge because normally by now much of the stubble from the wheat fields would have been grazed and, thus, the ground would be clear and surface survey easy because any sherds on the ground could be easily spotted. However, this season, several of the sites still had a 15cm or so of wheat stubble, making for poor visibility.

In our conditions assessment, we did find two sites that were reasonably clear of groundcover. One was Kharaba Tawuz, which you read about earlier. The other is an unnamed site known by its EPAS survey number as #290. I will introduce you to these sites, and the others, over the course of this blog. Being small sites, they are somewhat hard to see from the ground unless you know what you are looking for. A very subtle rise in the middle of the field may well reveal an archaeological site.

Photograph of Kharaba Tawuz taken facing west in the early morning. We took advantage of the low, raking light to create shadows on the site.

Above is a drone photo taken early this morning at Kharaba Tawuz. With the long shadows, you can see the small rise that comprises the ancient site in the plowed field to the left of the track. Aerial photography has been in use in archaeology for over a century. The drone and digital camera have replaced prop-driven airplanes and film cameras and have greatly improved our mapping of the ancient landscape.

Using Britt’s surface survey, and the site topography, as a guide, we chose an area for excavation that started off as a 2.5m by 2.5m trench, but has now expanded twice so that it covers three times that area. The top 40 cm is soil that was badly churned up by the modern plowing of the field. Below that, though, we found layers that were less disturbed and contained the first intact, in situ archaeological deposits of the Sebittu project, some possibly dating to the Iron Age. More to come on what we found.

On the ground.

One question that archaeologists often get asked is ‘how do you know where to dig’? It’s a good, logical question, and one which is answered differently depending on where you are working, which cultures you and what time periods you are interested in, and what your research questions are.

We are primarily interested in documenting village and farm life in the first millennium BC, so we want to find the houses, pits, hearths, and storage rooms that people used in the Iron Age. Rather than just randomly starting to dig, we search the surface as carefully as possible for any clue about what is below ground. Sometimes this involves looking at satellite maps and aerial or drone photographs.

This is a drone image provided to us by Jason Ur and his EPAS team at Site 275. The contour lines show the elevations at the site with white being high elevations. This images shows our survey points (marked with coordinates) an specific find spots of items on the ground. Drone photography has revolutionized the way archaeologists record the landscape.

Surface survey involves collecting the artifacts that are just lying on top of the surface of the ground, often pulled up by the plow during preparing the fields for planting. These artifacts, although they are not in the place where ancient people left them (a condition we call in situ), they still give us an indication of what is below ground.

Britt and Tara set up the survey grid with tapes and wooden stakes under the careful observation of Gareeb and Mary.

Sarah took these photographs of our survey at Site 275, which a local landowner said is called Kharaba Tawus (Kurdish for “Mound of the Peacock”). After we have laid out a grid of survey squares 20m by 20m with wooden pegs marking the corners, the team lines up evenly spaced and slowly walks across the square picking up pottery. Britt then determines which sherds can be dated (these are called “diagnostics”) and all the useful sherds from each square are bagged and tagged. Later, back at the dig house, Britt compiles a distribution map showing where the greatest concentration of Iron Age pottery is found. That is where we dig!

The survey line moves across the southern field at Site 275. Mary is closest to the camera here and Rafeeq is at the far end of the 20m line. Surface survey is hot, dusty work but it is an important way to figure out what’s below ground.